Date: 19th November 1940

Time: 21.09 hours.

Unit: 2 Staffel./ Kampfgeschwader 55

Type: Heinkel He 111P-4

Werke/Nr.2877

Coded: G1 + LK

Location: Workshop Farm, Wolvey, Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. (K.8807).

Pilot: Oberleutnant. Hans Klawe. 67016/111 – Killed.

Observer: Feldwebel. Wilhelm Gutekunst. 67016/30 – Baled out and captured.

Radio/Op: Unteroffizier. Rudolf Zeitz. 67016/138 – Baled out and captured.

Gunner: Gefreiter. Xaver Nirschel. 67016/138 – Killed.

REASON FOR LOSS:

Took off from Dreux. Aircraft hit by AA fire and when the wireless operator saw the observer bale out, he followed suit. Aircraft was completely wrecked and burnt out. Armament: Parts of one MG 15 and some pieces of armour found. Markings: A small plate found in the wreckage showed that the aircraft or component was made at Heinkel Werke, Oranienburg. Bomb load included at least one 500 kg bomb slung on the underside of the aircraft.

This Heinkel of 5./KG 55 suffered somewhat a similar infliction to that of the Wolvey Heinkel. On 25 September 1940

near Bristol, an AA shell exploded under the aircraft’s tail,badly damaging its controls, so the crew baled out.

(credit: Steve Hall).

The pilot and observer had a close working relationship in the cockpit, through good times and bad. Here, Fw. Hans Reiter

and Oblt. Hans Mössner are looking in a rather upbeat mood as they head off in their aircraft ‘G1 + EK’. Also in 2./KG55,

they flew with Oblt. Hans Klawe’s Heinkel ‘G1 + LK’ (credit: Steve Hall).

James Wearn tells the story of the ill-fated ‘Wolvey Heinkel’, the quest to find the aircraft, and modern remembrance;

“Das Flugzeug reagiert nicht! Aussteigen, schnell!” As a bomber crew realises their fate, and the aircraft descends uncontrollably, four men act desperately to save their lives and those of their companions. For two of them, this will be their last flight…

As the Battle of Britain came to a close in late 1940, the Luftwaffe’s attention turned to urban raids, in an attempt to cripple British industry and shatter morale. The lives of each German aircrew (as well as British civilians on the ground) hung in the balance every time they headed out on a mission. Cramped together in their flying metal hulks, they faced perils together, night after day.

Using eyewitness accounts, declassified reports, diary entries, recovered aircraft parts and discussions with members of the excavation team, it has been possible to piece together the poignant story of the ‘Wolvey Heinkel’ – from its point of take-off in 1940 to the present day.

This particular case is notable through the series of unfortunate events that dictated the fate of the aircraft and its hapless crew; as well as the rediscovery of the site of impact 45 years after the Heinkel fell to earth, which brought with it new discoveries from a Warwickshire field. Of all the aircraft shot down during the Blitz, this machine and its crew became a prominent feature in a recent regional commemorative event.

I picked up the trail following a chance encounter with one of the participants in the 1980s crash site excavation. One lead soon yielded another, and from each answer several more questions sprang forth. Suddenly it all began to come together…

Target: Birmingham.

On the evening of Tuesday 19 November 1940, the men of Kampfgeschwader 55 ‘Greif’ (Bomber Wing 55, nicknamed ‘Griffin’ in line with its unit emblem), prepared for a sortie to destroy armaments factories in Birmingham. The crews of I. Gruppe at their base in Dreux, 70 km to the west of Paris and 500 km from their target, clambered into their round-nosed Heinkel He 111 machines and began taxiing for take-off. Just eight days previously Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle had visited KG55 headquarters at Villacoublay, where he made several promotions and bestowed awards. Such visits were useful morale-boosters but Sperrle was under no illusion as to the difficulty of the tasks that were being set for his men.

Oberleutnant Klawe and his three crewmates (only four crew flew in each aircraft by night, and five [extra gunner] by day) had a cargo of 4 x 250 kg bombs and 1 x 500 kg bomb (the last held externally) ready for their aerial assault. The daytime hindrance of low-level cloud over England had passed, allowing a major offensive. Theirs was one of a total of 369 bombers from KG 26, KG 54 and KG 55 which were sent that night.

Oblt. Klawe’s aircraft had been scheduled to depart second or third within their Gruppe but their bad luck that night began as soon as they were moving on the ground. Whether overcome by tiredness from previous sorties or simply taking their eyes off the matter in hand, the aircraft overran the boundary lights and careered into an adjacent ploughed field, quickly sinking into the mud left from previous rain. They had lost their place in the starting line-up and ground crew were summoned to move the incapacitated machine. After a struggle, they managed to pull the Heinkel back onto the airfield and ready it for take-off once again. Perhaps this had been a prophetic sign to abort the mission from the start. Unfortunately for the crew, their error at Dreux was not sufficient for them to abandon their aircraft or mission, and so they began again.

Their false start behind them, pilot Oberleutnant. Hans Klawe, observer Feldwebel. Wilhelm Gutekunst, wireless operator Unteroffizier. Rudolf Zeitz and gunner Gefreiter. Xaver Nirschel successfully ascended to their airborne formation, now lagging further behind than intended, and headed towards to the English Channel and then north of London. Flying level at about 4,000 m (13,000 ft), the plan was to follow the audio signal of the Knickebein guidance beam, pick up the cross-beam and then to drop their load over the target. Preceding I. Gruppe were the aircraft of II. Gruppe, which illuminated targets by dropping flares. However, Oblt. Klawe’s crew didn’t make it that far, and found themselves floundering just short of their goal

.

The two members of the crew who were interrogated by British Air Intelligence branch A.I.1(k) recalled that their beam signal was variable, and over the Midlands they lost it completely. Soon after, they experienced problems with the aircraft’s electrical systems. The pilot and observer became disoriented because the artificial horizon indicator and compass were not functioning properly and the night was too dark to re-orientate correctly. The aircraft yawed violently and “the observer suddenly found himself pressed against the side, and concluded that they were slide-slipping” (A.I.1(k) Report No. 934/1940). The crew decided to released their bombs in the hope that this may help, but it did not, so the observer and wireless operator baled out.

The pilot and gunner went down with the aircraft, and were both killed in the crash. It could be argued that their accident at Dreux, which had delayed their take-off, played a part in their downfall because anti-aircraft defences in the Midlands had kicked into action by the time Klawe’s aircraft approached. There was heavy AA fire defending the city Birmingham and neighbouring towns, and this aircraft shoot-down was attributed to this artillery.

During the post-crash Allied interrogation, it was noted that: “The observer is rather critical of the pilot (an Oberleutnant), who had tried to take over the navigation and would not allow the observer to help”. But, of course, the pilot was no longer alive to defend himself. The observer said the pilot’s intervention could have caused them to lose the beam, and he blamed the pilot for not letting him help. The crew were experienced personnel, having taken part in several major raids that year: including Jersey, Yeovil and Coventry. Nevertheless, something seems to have been awry from the offset, as evidenced by the lapse in concentration back in France. Perhaps the taxiing error had caused tension between the pilot and observer, which resurfaced later in the flight.

Wilhelm Gutekunst had actually been spared death on two occasions during his service in 2. Staffel. It transpired that he had flown on several missions in an aircraft coded G1+HK, which had been shot down into the sea on 11 July. He was supposed to be the observer on that day too, but due to illness had been replaced by Uffz. Karl Maiereder, whose luck had run out. The entire crew of G1 + HK were lost. KG 55 continued missions over England until the end of May1941, and in June it was moved eastward to bases in Poland and then to Ukraine and southern Russia. KG 55 earned fame as one of the principal workhorses in the southern sector of the Eastern Front, both in the Caucasus region and later, for its part in the air-evacuation of troops of the trapped German 6th Army at Stalingrad. Notably, the geschwader continued to rely on its Heinkel He 111 aircraft throughout.

During the war a total of 60,938,211 kg of bombs and 7,514,390 kg of supplies were dropped by KG 55 during an impressive 54, 271 sorties by the geschwader! Unit histories by Dierich (1975, in German) and Hall & Quinlan (2000) provide excellent coverage of these endeavours.

Forty years on;

During the early1980s, several visits were made by wartime aviation enthusiast Philippa Hodgkiss to Workshop Farm (situated between Wolvey and Withybrook in Warwickshire) – the site where the Wolvey Heinkel was supposed to have crashed. This was to become the build-up to a major excavation. The research was directed by Philippa, who had carried out site investigations for the Warplane Wreck Investigation Group (WWIG) since the mid-1970s, and was eagerly aided by the late Peter Foote. Peter’s name will always remain inextricably linked with the genesis of aviation archaeology in Britain as he was out and about investigating crash sites even in the 1950s, having been a wartime schoolboy with an avid interest in such things!

In 1983 the investigation took a great leap forward when Philippa secured an interview with the (retired) farmer, Lionel Perkins. In the interview he revealed that he had been an eyewitness to the crash and, moreover, he knew (almost) exactly where the crash site was. He indicated that it was a few feet inside a grazing field, just beyond a line of boundary posts by its entrance gate. He described how his family heard something coming down and someone had thought it was an aerial mine, but he had thought it sounded much bigger. He was right. As the German bomber descended it crossed a searchlight beam and he saw two men bale out. It came over his wood yard and he worried that it would hit the house. Mr Perkins recalled that while his family were lying flat inside the house, the thought that ran through his own mind was: “We’ll never get up from here again”, especially when they heard a terrifying screech just before impact. “We all expected to blow up” he added. But, the aircraft just missed the house and crashed with a big explosion on the edge of a field close by. The impact “shook all the tiles on the house” he noted. The official crash time was recorded as 9.05 pm. Meanwhile the air raid on Birmingham raged on. The fire that night was extremely intense and repeatedly flared up from the wreckage, making exploration near impossible.

On the morning after, Mr Perkins went out to see by daylight what had occurred the previous night. He found a German flying helmet sitting in the field near his house, and still had it when interviewed in 1983 (when Mr Perkins died, his wife kindly gave this flying helmet to Philippa Hodgkiss, on the understanding that it would be donated to a museum). He also said that he had found a few scattered parts of one of the unfortunate men killed in the crash, which he placed into the wreckage fire to cremate them altogether. Whether compassionate or pragmatic, his action meant that there appears to have been nothing left for contemporary burial.

In addition to attendance at the scene by the usual emergency services, a war correspondent interviewed Mr Perkins, though little was learnt from the wreckage at the time – the depth of the impact was so great and the fire so persistent. According to Mr Perkins, the recovery crew spent about two weeks inspecting the crash site. Apart from the persistent fire, the force of impact had buried much of the aircraft so they didn’t lift the heaviest parts, getting down to about 20 ft (6 m). Initially, only some pieces of armour and part of an MG15 machine-gun were recovered, then as work continued many of the lighter items were retrieved and removed.

Some later interest had been show in the site 15 years before Philippa’s investigation, but that was merely superficial metal detecting in the field. Deep excavation would be needed to find out anything useful in this case. By 1983, nothing out of the ordinary was visible on the surface of the field. A horse gently grazed the pasture whilst birds fluttered in the hedgerow. Such a scene of serenity belied the twisted wreckage – fragments of a tragic evening – which were buried beneath. Following the eyewitness interview, Peter Foote noted in his diary: “from what she was told it looks well worth digging.” Contact was then made with fellow enthusiasts, including the local museum (Fort Perch Rock Museum, Merseyside) where WWIG’s collection was held. Mr Woolley, the landowner, kindly gave permission for the dig to proceed.

The day of the dig, 22 September 1985, finally arrived. An overcast but dry day greeted the team. Philippa and Peter were on site by 10.00, and were soon accompanied by the other participants, totalling about 14 people (although at first it was feared there may be ‘too many cooks in the kitchen’), supported by a few local residents on the periphery who had turned out to witness the event…along with a very useful mechanical digger.

As the turf was scraped away, anticipation was high. Several of the team had plenty of experience already but every site yields new intrigue and new evidence, so the excitement is renewed every time. Nothing was found in the original spot by the gate previously indicated by Mr Perkins, but undeterred and by adhering to the universal principle ‘if you keep digging and don’t find anything, move a little to the side’, fragments of fuselage began emerging just off to the right of the starting point. The soil was hard clay but they persisted. Digging ever deeper, heavier components were unearthed. Meanwhile, tales about the crash and aircrew were relayed to members of the dig team, mostly based on hearsay, so it became necessary to separate fact from fiction.

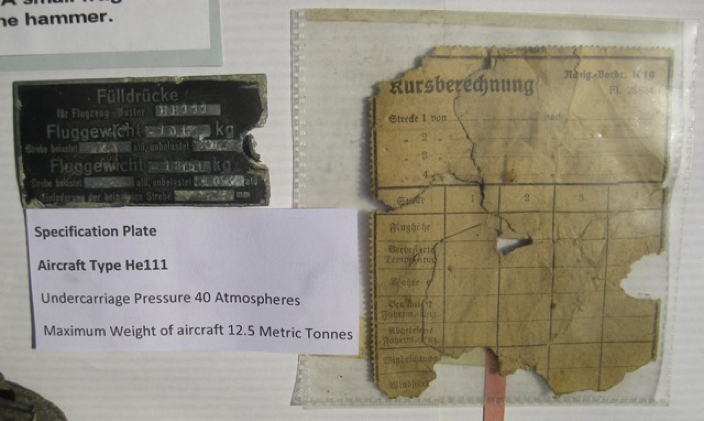

Both smashed Daimler-Benz DB601A-1 engines were recovered along with chunks of crankcase and engine mounts, propeller hubs, main wheels, the handle of a flare pistol, a sign giving instructions for operating the undercarriage (which would have been mounted on the bulkhead behind the Observer), as well as fragments of fuselage and smaller components. Sealed in clay at the bottom of the hole was a torn form entitled ‘Kursberechnung’ (Course calculation), which would have been in the observer’s possession during the flight. It was blank and so likely a spare. There were a number of 7.92 mm MG15 casings from the defensive armament, many of which had obviously exploded during the crash fire. No human remains were found during the excavation. It is probable that the unfortunate pilot and gunner were cremated in the intensity of the fire in 1940, and subsequent disintegration had removed any traces.

Perhaps the most important finds were data plates confirming the aircraft type, while the DB engines provided supporting evidence of the aircraft model being an He 111P-4, fewer of which were employed than of the Junkers Jumo-powered He 111H. Of particular notes was a data plate bearing the aircraft’s individual Werknummer (works production number) ‘2877’ and date ‘1.40’. This provided certainty of finding the aircraft the team were looking for (discovery of ‘unexpected’ aircraft is not unknown!). Finally, a compass dial with information scratched by hand into the data box read: “Flugzeug G1 + LK”. The Wolvey Heinkel, is widely thought to have had the identification code G1 + LK (including A.I. Report 934/1940 from the aircrew interrogation and Hall & Quinlan 2000), although G1 + CK has also been recorded (Dierich 1975). At first the ‘LK’ scratched into the aforementioned dial was misread as ‘CK’ but under a hand lens it became clear as ‘LK’. Some uncertainty persisted even among those who had been involved in KG 55 research and had consulted original documentation; thought to have been a case of mistaken transcription at some point of a curly ‘L’ which appeared like a ‘C’!

Panoramic view of the site towards the end of the dig in 1985, with wreckage sorted into piles.

A small group to the left inspects one of the Daimler-Benz engines (credit: Philippa Hodgkiss).

In the hole: more than six feet down, the team discovers some heavier parts (credit: Philippa Hodgkiss).

One of the tyres which got stuck in the mud at Dreux after the Heinkel’s first accident on the fateful night.

A rather deflated, but nonetheless poignant, piece of its history (credit: Philippa Hodgkiss).

A chunk of DB601A crankcase with engine bearer mount and retaining some of its original paintwork

(credit: James Wearn).

Wheel trim showing tyre size, pressures for different loads and VDM (Vereinigte Deutsche Metallwerke AG)logo.

The characteristic KG55 Griffin emblem has been added for display purposes (credit: Philippa Hodgkiss).

One of the Heinkel’s data plates and Kursberechnung document,

forming part of the display of artefacts which featured in the Birmingham Blitz commemoration event in 2010

(credit: Philippa Hodgkiss).

Reflection on both sides;

In 1951 the ‘Kameradenkreis’ (Comrades’ circle) of KG 55 held its first post-war reunion. A total of 27 former members of the unit attended. Wartime aviation historians Steve Hall and the late Lionel Quinlan carried out extensive research on the unit and compiled a photographic history containing numerous previously unpublished images. This brought them into close contact with many of the surviving veterans and their families. Unfortunately, no photos of the aircrew of Wnr. 2877 were found during their search (Steve Hall, pers comm.). In 1976, they were made honorary members of the KG 55 comrades association.

As time went by, inevitably witnesses of the Wolvey Heinkel’s fall to earth passed away. Philippa Hodgkiss had realised this back in 1983, commenting on tape to Lionel Perkins: “What you remember, no-one else will ever be able to tell me”. Thanks to Philippa and her team, a large volume of data concerning the fate of the German bomber and its crew was recorded before it would have been lost forever. Notably, had it been three years later, this dig would not have been allowed to proceed as it did, due to the passing of the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986. Prior to this, the Ministry of Defence had relinquished its claim on crashed aircraft. The remains of two airmen were potentially still somewhere in the ground at the site in 1985, and so it would have been restricted as the last resting place of two servicemen. It is not known whether any remains were found by the recovery crew in 1940 (other than by Mr Perkins) and buried close by without a marker (though no report or eyewitness account of such has surfaced) or whether they were, as had long been believed, cremated in the burning wreckage. Nevertheless, to our knowledge there is still no marked grave for them anywhere in Britain.

In 2001, Peter Foote passed away, ending an era. Fortunately the extensive and meticulous notes of this remarkable man were left in Philippa Hodgkiss’s care. Two years later she took a trip to Dreux, and included a photo in her notes with the caption: “These old buildings would have been familiar to the crews of KG 55.” This effectively tied-up their research.

The artifacts from the crash site have ended up in several different collections. Several of the major aircraft components went to the Fort Perch Rock Museum. The remainder of the recovered material was distributed among the team members, as was customary on digs of this period. Though in common with other digs at the time, there was a ‘scramble’ for the most prized pieces. Indeed Peter Foote always had a critical eye, and in typical form he grumbled in his diary after the dig that a couple of the participants had “acted like vultures”!

A few of the items from Heinkel 2877 have now passed to secondary enthusiasts, but it is hoped that the most significant finds will one day find a more permanent home together in a local museum so that this story can be told with a more complete complement of visual stimuli.

The ‘Birmingham Blitz’ was remembered on 19 November 2010 in a commemorative event held to mark the 70th anniversary of the heaviest raid on the city. Indeed, Birmingham was the second most heavily bombed city after London. That destructive night was a special feature of the commemoration, as was a display of selected artifacts from the Wolvey Heinkel. Following a wreath-laying ceremony, the display case was held aloft during a procession and then put on show at the Birmingham Council premises. The event booklet stated: “And finally, seventy years on to the day and almost the hour some remains of the aircraft which almost reached its target were displayed at the Banqueting Chamber of Birmingham’s Council House, whilst below, outside the tall windows behind the case, shoppers and revellers thronged the German Christmas Market” – an unequivocal tribute to post-war international unity.

Further reading;

Dierich, W. (1975) Kampfgeschwader 55 “Greif”. Motorbuch-Verlag. [reprinted in 2012].

Hall, S. & Quinlan, L. (2000) KG55 Greif Geschwader. In focus. Red Kite.

Ramsey, W. (1988) The Blitz. Then and now. Volume 2. After the Battle Publications.

Wearn, J. (2012) Picking up the pieces. The Armourer 114: 28-31.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Philippa Hodgkiss (and the Peter Foote Archive in her care), and also thank Steve Hall, Doug Darroch (Fort Perch Rock Museum), Colin Lee, Steve Vizard, and the National Archives, Kew.

Burial details:

No burial detail can be found for those who lost their lives on VDK website.

Compiled by Melvin Brownless on behalf of Philippa Hodgkiss and James Wearn, May 2015.

The British Library is preserving this site for the future in the UK Web Archive at www.webarchive.org.uk All Aircrew Remembered on our Remembrance pages, are therefor not just remembered here, but also subsequently remembered and recorded as part of our nation’s history

and heritage at The British Library.